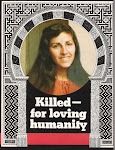

This is the moving account of the martyrdom of Zarrin Moghimi Ebayaneth in June 18,1982, a Bahá’i girl who was only 28. It is written by her sister, Simin Moghimi, and translated from Persian by Mozhgan Baher.

Her sister wrote: “ Zarrin Moghimi was born in 1954. Her mother, who did not expect the child to be born so soon,

had gone to her own birthplace. Ebyaneh, for a short stay. There Zarrin was born. Ebyaneh is a beautiful village at the foot of the mountains between Isfahan and Kashan, two Persian cities. Zarrin became very fond of this village. Since the early days of the Faith, there had been Bahá’i in the village and Zarrin’s grandfather had become a Bahá’i there.

Zarrin was the third and last child of Hossain and Salehi Moghimi. Until she was 21, when she finished her education, she lived in Tihran. After that she joined her parents in Shiraz, where her father was responsible for keeping the House of the Báb in good repair. She continued to live in Shiraz until she was martyred at the age of 28.

From early childhood, she had a warm and expressive voice. I remember when she was only 5, she would stand on a chair and recite poems in the Bahá’i meetings. As she grew into her teens, her love of the Bahá’i cause became more and more evident.

One Friday, when she was 12 years old, her parents suggested that she should not go to the Bahá’i moral classes that week because there was a heavy snow, the road was closed, and there was no transport. Zarrin started to cry, saying: ’If I don’t attend the moral classes because of snow, how will I ever be able to serve the cause in the future ?’ So her mother had no choice but to walk with her all the way to where the classes were held.

On another occasion, when I was very sad because some of her friends had called her ‘a mulla’ and ‘a fanatic’ when she had refused to go with them to a dance party, she reassured me, saying :’Do you know that, according to Ruhiyyih Khanum (wife of Shoghi Effendi), living in accordance with Bahá’u’llah’s laws and exhortations in this age is like swimming against the current of a river? Moral standards have changed drastically and people are bewildered, unable to tell the difference of good and bad. So we need to straighten ourselves and be ready.’

Zarrin loved to read. She was usually awake past midnight, reading. She followed a simple and beautiful style in her writing and her love for the faith was clear in everything she wrote. She was almost always first at high school and university – he obtained wonderful marks. She memorized Bahá’u’llah’s Kitab-i-Aqdas fully by heart and her copy of the Holy Qur’an was extensively footnote on the verses.

At the age of 15, she became a teacher at the Bahá’i moral classes. She loved the storied of the faith’s martyrs and taught the stories to the children. This love was clearly shown in a piece she wrote after the martyrdom of Dr. Anvari and Mr. Dehghani:

‘O my God, how shall I ever be able to believe this has happened? I had heard stories of self-sacrifice only from Nabil’s history. I had thought I should have to travel back through the gates of time to 137 years ago to understand the meaning of sacrifice. But lo, the Divine Will decreed otherwise and I witness with my own eyes the secret of self-sacrifice. Believe me, I saw the Abha Kingdom and blessed angels scattering flower petals on those heavenly souls (the martyrs)…

Undoubtedly, this was a part of the Abha Kingdom itself.’

I remember that Zarrin was extremely kind, sacrificial. Softly-spoken and generous. One day, when we were ready to go out, Zarrin gave up her plans without the least complaint so that she could remain at home to look after her grandmother.

When she was scarcely 15, she wrote about her parents, calling them ‘her treasury’. ‘If we were allowed to choose our own parents, how could I ever find a better father? She then proceeded to praise her father as an artist, and poet and a sculptor. Then she praised all her family members and rendered thanks to the All Merciful for such a ‘precious treasury.’

There was great love between her and her father. They would sit for hours together and discuss the truth. Though she tried to live in the utmost simplicity and had little regard for the material benefits, she still dreaded the claws of materialism. Once I wrote to her in a letter from England: ’You are not aware how much people’s time and especially that of children is spent in front of the TV set over here’. She replied : ’Here we are fortunately free from TV and its bad effects. Everything is of course, desirable in moderation. Whenever we become too attracted to material things, something comes up to shake us and remind us that we are still living in the age of sacrifice, and it is then that we pray to Bahá’u’llah to make us steadfast and not put to shame in time of tests.’

Along with her studies at the university, Zarrin continued studying the Bahá’i writings and completed a four-year deepening course conducted by Dr. Ghadimi. After graduating, she could not wait to go pioneering for the faith but, unfortunately, she was unable to move inside or outside the country.

It was her great desire to go to Ebyaneh, her birthplace, and teach in the schools there. The residents of Ebyaneh welcome the idea but the Government refused to allow her to do so because she was a Bahá’i and at that time job vacancies were abundant in Tihran. Yet she chose to go Shiraz rather tan remain in the capital and started working as a translator, accountant and administrative assistant in the petrochemical factory, but her heart still burned with the desire to go pioneering.

Dr Ghadimi, her eminent teacher, presented her with a gift to be opened when she was eventually reached her pioneering post. This gift still lies unopened on her windowsill, even after her martyrdom. In a letter to Dr. Ghadimi she wrote:’ I know I am an unworthy student. One who never deserved to be in those classes, that holy threshold which was the place of education for many of the great personalities in the faith, and that it was merely the mercy of Bahá’u’llah to have given me the privilege of attending those classes. I had taken an oath to write to you only after having done some service to match all those efforts you undertook to prepare us for serving Him. I thought your precious time would be better spent in writing to the dear pioneers who left everything for His beloved cause or in educating those who will follow that path in future. Yet what could I do? That day never dawn, despite my long waiting, the day when I could

write to you without feeling ashamed. That’s why I did not write to you for nearly five years’.

For two years Zarrin burnt with the anxiety of not, in her own estimation, having rendered any service to the cause. Then she had a beautiful dream. ‘I dreamed Bahá’u’llah came to the House of The Báb in Shiraz.’ She told me. ‘All the Bahá’is went to visit Him. I wanted to, too, but I did not dare to enter. Instead I stood near the door. I saw Bahá’u’llah with all the Bahá’is paying their respect to Him. Finally they finished and left one by one, but I still stood there. Bahá’u’llah stood up to climb the steps. I thought to myself, ‘Woe to me. Even at this moment, when there is an opportunity, I do not deserve to go and see Him’. Then suddenly Bahá’u’llah turned His face to me and beckoned me to come in. I entered and went up to Him. He embraced me and put my head against His heart. Then, putting His hand on my head, He said ’Why are you so perturbed? You will finally achieved your desire’. After this dream Zarrin was calmed.

As her father was in charge of repairing the House of the Báb, they took up residence in a nearby house belonging to the Bahá’i Faith. Zarrin fell in love with Shiraz and that beloved lane. When ever she went to visit Tihran, she would be restless, wanting to return to Shiraz. She always said that Shiraz was better for her from the spiritual point of view. The day on which Mr. Khoshkhoo, Mr Vahdat and Mr. Mehdizadeh were martyred in Shiraz, Zarrin was in Tihran. When she heard the news, she returned to Shiraz the next day.

At the time of the destruction of the House of the Báb, Zarrin was an eye-witness to the tearing down of every brick and many times she argued with those in charge of the demolition. Regarding this event, she wrote in a letter:

“The destruction of the lane has advanced. One can’t believe that there was ever a roof or a narrow lane there. Right now I can hear the sound of the trucks. Nothing has remained of our old familiar lane and instead there are heaps of dust, empty space and half demolished walls. It is a strange feeling. A few nights ago, when I was passing the ruins, I had a feeling that even the dust of this lane speaks of love. When I stood to look at the ruins, the whole scene spoke of the greatness of the Báb. What power did He have that they dread even the dust of His threshold and hurry so much to extinguish His relics?

‘ Many people come to look at the ruins. It feels as though one has travelled back to the heroic age. You are truly missing this. It is, of course, a part of God’s Will that it should happen so. We should strive only to strengthen our resolve and remain steadfast whatever happens. At present, there is nothing we can do except pray to His Holy threshold and supplicate Bahá’u’llah to give us steadfastness, worthiness and capability to pass through such an historic stage of the faith, and enable us to come through such tests and trails successfully. You are missing the wonderful prayer meeting we hold here.’

I wrote to her that we visited the Shrine of the Beloved Guardian, Shoghi Effendi, in London and prayed for the Bahá’is in Iran. She replied:” You have written of your visit to the Holy Shrine. How fortunately! We too visit the ruins of the Beloved House over here. This morning when we went out with father, we passed the place where the House of the Báb had been and, as we went by, I put my foot on a stone on which were stuck a few pieces of tile. Suddenly father said, “Do you know you have just put your foot on a part of the hall of the House of the Báb?’ The spot which was once washed with tears of pilgrims was now under our muddy boots.

‘Thus the Báb teaches us the lesson of sacrifice. He has let His house fall into the hands of enemies so that we may learnt not to care about out material belongings, He made His heart a target for the darts of enemies to teach us the lesson of self-sufficiency.’

The house where Zarrin and her parents lived was on the other side of the lane. Although it was not included in the plan for demolition, life was made very difficult for the family. They could have gone to their house in Tihran right from the beginning but because of their great love of the beloved old lane and for Shiraz and because the local assembly had asked the Bahá’is, as far as possible, not to leave their houses, they decided to remain.

On government orders, water and electricity were cut off. Many of the gypsies in Shiraz, who lived in the caravanserai, attacked their house, occupying the basement and some of the upper floor. It left Zarrin and her parents to live in two rooms. Among those gypsies was a drug addict who stole something from the house everyday to sell for money for drugs.

Zarrin and her parents tried to find another house but, as though the Will of God decreed otherwise, each time they found one there was a problem which would delay them leaving their home.

About these times, Zarrin wrote: ’Water and electricity remain cut off as before. We fetch water every other day. They have broken through the basement wall to the next house which is, in turn, connected to another house where there is a water tap. A pipe is passed through the holes. When in our turn, Mother gets up at four in the morning, lights a lamp and goes into the basement. She waves the lamp and the second house knows we are waiting for water and passes the pipe through to our house. Though these are difficult times, yet I think they are the most precious days of our lives. We only pray for firmness.’

In another letter she wrote: ’The intruders are still here. They thought that as soon as they invaded us we would move from our house because they themselves knew how difficult it would be to live with them. Now they are surprised to see that seven months have passed and still we have not moved.’

After the Revolution in Iran, Zarrin lost her office job because she was a Bahá’i. “There were eight Bahá’is in our office,’ she said. They called us one by one to make us admit that we were Bahá’is and, as far as possible, guide us back to their so-called right path. All eight firmly proclaim their belief and courageously none renounced the faith. The news spread all over the office.

”I was the last to be called in and for around 20 minutes I talked with my boss about the faith. Since we spoke loudly, those in the adjacent room heard us too. Next morning when I went to the office, one of my colleagues said,’ I heard you recite Qur’anic verses to the boss yesterday.”

‘On the day when I was actually dismissed and wanted to say goodbye to my colleagues, they were all sad and girls wept. One of the girls was crying so much that I was unable to calm her down. One of the department heads, under whom a few Bahá’is served, said, “Although you are outwardly leaving us, you will remain in our hearts forever. “ Another, while shaking hands with me, said, “I appreciate your moral courage.; It was a very interesting day. I felt that on that day I received the reward of all those days I had worked. Never had I seen such an honorable dismissal.

Since the martyrdoms had begun in Iran, Zarrin had ‘died’ with every martyr, I remember when she heard the news of the martyrdom of Colonel Fahandesh from TV, she stood up from the chair, went into a corner and wept aloud. In another letter, to her teacher, Dr. Ghadimi, she said about the martyrs: “It is a strange situation. On one side, there is a sorrow of separation from the martyrs and, on the other, there is a courage, greatness and sacrifice. On one side, the memory of those radiant faces burnts the heart and, on the other, their self-sufficiency baffles and bewilders the mind.

‘ It is as though we were back in the heroic age (of the Bahá’i Faith) and the loud cry of the heroes of Nabil. “Is there anyone to see me?” was resounding in the ears of those drunk with the wine of ignorance. Never did I imagine that in my own lifetime I would be a witness to such events.’

After the martyrdom of Dr Avari and Mr. Dehghani, in the minutes of the Youth Committee, of which she was secretary, she wrote: “If we were to render thanks unto His threshold till the ends of our days, we should still fall short of praising Him enough for such a great privilege. How could we worthless creatures, like birds whose wing are stuck in the mire of dogma, be worthy of witnessing a part of the greatest event in history? It is as though the great souls of the unseen world drew us out of the routine of our everyday life, which we mistook for service, and sounded a great trumpet in our ears, ‘Lo and behold, this is the greatness of the Blessed Beauty, Bahá’u’llah. This is service, courage and, finally, martyrdom….’

She went on : ‘The 88th meeting of the committee never ended. Rather it end was a start, a start and a beginning for a generation of youth who had heard about the greatness of the cause but had never seen it, who had read the great holy epics but yet had never felt them. It as a beginning for generations to come who will read the famous names of the martyrs of Shiraz, Anvari and Dehghani, know for a certainty that no hurricane an ever put out the fire of divine love, and hear the clarion call of the martyrs to their beloved, “A world-embracing beauty deserves a world-consuming love”.’

Zarrin had a great love for Martha Root. When asked which of the early Bahá’i believers she would have liked to be, she answered: ‘Miss Martha Root because she did not stop thinking about teaching (the Bahá’i Faith) even for a single moment’. On one occasion, when we were talking together about the future Golden Age, in which Bahá’i believe, and how life would be then, she said: “ I have never wished to live in the Golden Age because then all that had to be done will have been done and the possibilities for teaching, available now, will be practically non-existent by then’.

In her last years Zarrin visited the Bahá’is in prison and also conducted three different moral classes. She describe her visit to one of the prisoners:

‘You do not know a different world exist there. Once you enter the prison, you feel how worthless the outside world is. The world of the prison seems close to the Abha Kingdom-almost too close, so much so that the faces of the prisoners shine with a strange light. I felt they look at us from another world, from a world where materialism has totally lost its value. I was speaking with one of the prisoners and he told me, “Do you see, I finally attained my heart’s desire,’ and his eyes shone. Faced with the greatness of his soul, I felt worthless and significant. I knew then that the banner of the cause is carried by these obscure heroes and we are only spectators and onlookers, observers of their bravery. I can never adequately express what feelings I had then.’

She refused to get married because she felt she could not think of anything except the cause. When I suggested to her over the phone that she leave Iran while she could, she said: ‘Why do you say that? Don’t you know that time is short, manpower less, and the work plenty? What happens to the other Bahá’is will happen to me too. My life is not more precious than theirs. I will never leave this country.’

In another letter she wrote;: ‘ Nowadays I have a lot work. There are meetings, study and moral classes to be held. At present, there is rare opportunity for service, I hope Bahá’u’llah will confirm our steps in His path…’ and ‘ We went through strange days, I mean regarding the House of Báb. We did a lot of teaching. This is all the will of God and leads to the progress of the Faith. It has always been the case that the opponents of the Faith serve best to proclaim it.’

Finally, in December, 1982, Zarrin was taken to prison, along with her parents and other Bahá’is. At midnight the Revolutionary Guards invaded their house, arrested them and took them to jail. Four months later Mother was freed.

Then one day when Mother was fasting and preparing to leave the house to visit her husband in the prison, the guards again invaded the house and put all the furniture and belongings out the road. Mother wrote to me, ‘Your father and Zarrin are keeping up their fine spirits. I don’t know why but whenever I visit Zarrin she says to me, ‘Don’t be hopeful about my release. Give me up. Prepare yourself….”

One of Zarrin’s appearances in court lasted for 11 hours, during all of which time she was blindfolded. This was while Mother was in prison too. Seeing that her daughter had not return after such a long time, she fainted. When she regained consciousness, she found Zarrin by her side. For the trails, the prisoners were blindfolded and guided by a rolled newspaper, the other end of which held by a guard who led them to the courtroom.

One of the Bahá’is who was latter released described Zarrin’s court appearances: ‘During the many trials that Zarrin had to undergo, she held back nothing. She acknowledged the truth of all the past religions courageously and also expressed her firm belief in the new Manifestation of God, Bahá’u’llah. Because she had so demonstrated her knowledge during the trails, the judges became afraid and flabbergasted.’

Zarrin herself describe what happened: ‘During long and repetitive appearances, one day, as usual, they blindfolded me and took me to the courtroom. Contrary to the other days when I had to write answers to their questions, this time the interrogations were carried on orally. For a long time I was asked questions mostly based on my beliefs. I answered them all, quoting verses from the Qur’an. Suddenly, I heard the judge who was interrogating me saying to the others, ‘Any of you who has any question may please ask. I am helpless and overpowered. What will you ask her now? She confesses that she is Bahá’i and that, according to the verses of the Qur’an, the Promise One for whom we are waiting has appeared. Any of you who has a question or an answer to give please come forward.’ There was not a single question and I felt people were standing up. Then I could hear the sound of the receding steps.

‘I said to the judge who had interrogated me, “You have blindfolded my eyes, I have no way of knowing what is happening around me. How many people were here?’ The judge replied, ‘I have interrogated you several times. When I spoke about your courage and the extent of your knowledge to the other judges, they did not believe me. Therefore, I asked them to come here today and listen for themselves, give their judgment and pass their verdict.’ Then the judge asked me, ‘What verdict do you suppose we will pass on you?’ I replied. ‘At the worst, the death sentence but, be that as it may, I preferred to tell you the truth and what I believe in, rather than be held responsible for failing to do so in the court of divine justice in the world hereafter’.’

Later when she was taken for her final court appearance, the judge told her, as he told all the others: ‘Either you renounce you faith or it is the death sentence for you’. Zarrin replied: ‘I have found the pathway of truth and under no circumstances will I ever give it up, and I, therefore, embrace the verdict of the judge’.

They asked her: ‘How far are you ready to stand by your beliefs? Will you remain so firm if it spells your execution?’ Zarrin answered immediately; ‘I hope to remain firm and steadfast until my last breath.’

The judge repeated his questioning. This repetition was disagreeable to Zarrin who said: ‘For many days you have been interrogating me. I have expressed my beliefs categorically. I think there is no need for me to repeat any further’. The judge persisted and Zarrin started to cry aloud: ‘With what tongue can I tell you? Why don’t you leave me? My life is Bahá’u’llah. My love is Bahá’u’llah . My heart is Bahá’u’llah. The judge was furious and restored: ‘ I will pull out your heart from your bosom’. Zarrin replied: ‘Even then, my heart will cry out and shout the name of Bahá’u’llah.

Greatly impressed by this, the judge left the room. On his return he saw Zarrin was still crying, at which he said: Madam, we are human beings too, we have feelings’. Zarrin said: ‘How else can I tell you? Have I not told you time and time again? How can one deny the truth?’

Zarrin was known as the Bahá’I teacher in the revolutionary court of Shiraz and she feared no danger. She truly considered herself as one who had staked her whole life and, far from losing it, had found life more abundantly.

A fellow-prisoner who was later released wrote to me: ‘One night Zarrin and I were walking in the corridor of the prison, talking about the interrogations. After two hours of talking, Zarrin turned her face to me and told me with great fervor, “Will my long-felt desire to teach the Faith but one person and to make him a believer during my life time remain for ever only in my heart? Does Bahá’u’llah not even consider me worth that much?’.

I felt I knew the answer to this question when I learn that in a meeting held in her memory in Brighton, England, one person has become a Bahá’i. Mother told me later that Zarrin had a pure white scarf which she kept in the prison, washed and ready to be worn on the day of her martyrdom. But unfortunately, when that day arrivedafter meeting with her family members for the last time,he and her fellow martyrs were not brought back to their prison cells but taken directly to the field of execution. After eight months of oppressive and intolerable imprisonment, Zarrin welcome death singing songs with her friends, and their pure souls ascended to the external kingdom of glory.

Her close friend in prison later wrote to me: ‘Zarrin always knew that she occupied a special place in the hearts of all who knew her, particularly her friends and relatives. With her faultless conduct and behavior, truly she was that exemplary human being described in the writings of Bahá’u’llah.

After Zarrin’s martyrdom, Mother told me over the phone: ‘ On Saturday, June 18, I went to see Zarrin as usual. I had taken her some fruit. It was unbearably hot. At the appointed hour, they brought Zarrin to the other side of the glass. While we talked, both of us were wet with sweat and Zarrin’s face was not the same as usual. She told me, ‘Mother dear, do pray and ask God for steadfastness’. Because she couldn’t see my distress, she did not say goodbye. As she had always told me not to have any hopes for her release, it never occurred to me that they might have taken them for their last appearance in court or might have planned their execution.

‘The visiting hour ended and I return home. Early Sunday morning I learned that on Saturday, after the visiting hour, they hanged ten of the women prisoners. I rushed to the house of one of the Bahá’is to ask if they knew the names of the new martyrs. They didn’t. I rushed from there to go elsewhere and ask. On the road I saw three of the Bahá’is with tears welled up in their eyes. They knew. One of them took out a paper from his pocket—I knew that Zarrin had been martyred too.

‘Crying and groaning, I hurried to the prison which we had regularly visited during the last eight months. They let me enter the mortuary. I did not think I could go on living after seeing that scene at that historical moment. How the day passed for me and what these eyes saw is certainly unexplainable. I shall never be able to describe adequately what I saw at that time.

‘I went into the mortuary and behold—there were ten angels sleeping next to one another. I knew them all. I have been in prison with them. Mother and daughter lay side by side. They wore simple cotton pants and shirts. Some had their chador still tied around their waist and other had slipped to the floor. How was I still breathing? And I was still on my feet? I failed to understand. I looked at all ten. I saw Zarrin was in their midst. She was laying there calm. I embraced her cold body and put my cheek against her cold and soft face and on behalf of you all (Father who was still in jail and my brother and I were abroad) kissed the mark of the ropes on her dear, delicate neck. Her face was most calm and natural.’

Zarrin had charged all her friends in prison to tell everyone: ‘Nobody should wear black for me or cry loudly. Only my mother may cry a little because I know that otherwise she cannot bear it.’I end this account here, but the memory of Zarrin Moghimi remains eternal and everlasting. “From Simin Moghimi

The names and ages of the other women who were hanged with Zarrin are:

Mrs. Nusrat Yalda'i, 54 years old,

Mrs. 'Izzat Janami Ishraqi, 50 years old,

Miss Roya Ishraqi, 23 and daughter of 'Izzat,

Mrs. Tahirih Siyavushi, 32 years old,

Miss Shirin Dalvand, 25 years old,

Miss Akhtar Sabit, 19 or early 20's,

Miss Simin Sabiri, early 20's,

Miss Mahshid Nirumand, 28 years old,

Miss Mona Mahmudnizhad, 17 years old.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Thank you very much Eric for sharing this moving account.

ReplyDeleteOne correction however is in order: I believe the date should be 18th June 1983 instead of 1982. This must have taken place during conversion from Persian to Gregorian calendar.

Thank you once again.